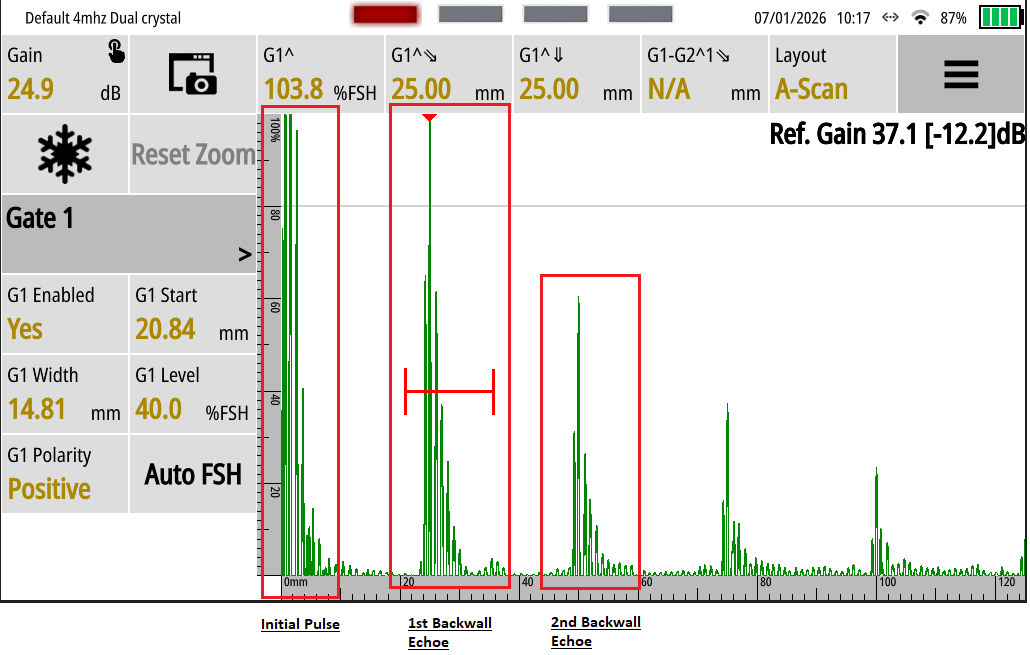

The first significant trace corresponds to the transmitted pulse (the initial excitation), and subsequent peaks indicate reflections from internal features or the back wall.

In a defect-free specimen of uniform thickness, the backwall echo typically appears at a predictable time. A defect generates an earlier echo, its relative amplitude, and time delay give clues to size and depth.

How do ultrasonic waves interact with materials?

Three interactions determine UT performance:

- Reflection and scattering - when an ultrasonic wave encounters a boundary between materials with different acoustic impedances, a portion of the energy is reflected toward the transducer. Perfectly planar, perpendicular interfaces give strong specular echoes, while rough or inclined discontinuities scatter energy more diffusely.

- Refraction and mode conversion - at interfaces where the incident beam is not perpendicular, waves change direction according to Snell’s law for acoustics. In solids, an incident longitudinal wave can convert partially to shear motion at the boundary.

- Attenuation and dispersion - as waves travel, they lose energy through absorption and scattering. The loss of clarity increases with frequency and with microstructural anomalies such as coarse grain, porosity or micro-cracking. Dispersion can alter wave shape and complicate timing measurements, especially over long paths or in anisotropic materials.

Wave modes

Different wave motions are suited to different inspection challenges:

- Longitudinal waves - particle motion is parallel to propagation. These travel fastest and move through solids, liquids, and gases. They are well suited to thickness gauging and to detecting volumetric defects at normal incidence.

- Shear (transverse) waves - particle motion is perpendicular to propagation. Shear waves only exist in solids and are slower than longitudinal waves. They are particularly valuable for weld inspection and for detecting planar flaws such as cracks because they can provide higher sensitivity to such discontinuities when used with an appropriate angle beam.

- Surface (Rayleigh) waves - confined to the near-surface region, surface waves decay exponentially with depth. They detect surface and just-below-surface defects and characterise near-surface layers.

What methods and techniques are used in ultrasonic testing?

The choice of method used in ultrasonic testing depends on the component geometry, material, defect types sought, and the operational constraints.

Basic testing methods

There are two basic signal modes that govern most ultrasonic work:

- Pulse-echo mode - a single transducer transmits a short pulse and then receives echoes from internal features and the far surface. This is the default for thickness measurement and for locating reflectors from a single-access surface. It is flexible, simple to deploy, and provides time-of-flight information that converts directly to depth when sound speed is known.

- Through-transmission (attenuation) mode - this uses separate transmitter and receiver transducers placed on opposite sides of the workpiece. The receiver measures the transmitted energy, and an attenuation or local loss of signal indicates a discontinuity that interrupts or scatters the beam. Through-transmission can detect poorly reflective defects that give little backscatter, but it requires access to both sides of the part and provides no direct depth coordinate without scanning geometry or additional processing.

Application techniques

There are a number of application techniques applied to ultrasonic testing:

- Contact testing - the most common field technique. The probe is placed in direct contact with the part using a couplant. Contact testing supports straight-beam inspections for thickness checks and angle-beam inspections for welds and crack detection.

- Immersion testing - the component, transducer or both are immersed in water which serves as the couplant. Immersion testing produces consistent coupling and enables automated scanning with high repeatability.

- Air-coupled and non-contact techniques - allows inspection without liquid couplants, valuable where contact is impractical or damaging. It commonly operates at lower frequencies to accommodate the larger impedance mismatch and attendant attenuation. Electromagnetic Acoustic Transducers (EMATs) generate ultrasonic waves without a liquid couplant by using magnetic fields and Lorentz forces, and are especially useful for hot surfaces, rough finishes or coatings and for avoiding surface preparation.

Additionally, there are a number of advanced UT techniques used in more niche scenarios:

- Phased array ultrasonic testing (PAUT) - PAUT arrays consist of many small elements that are pulsed with programmable time delays to steer, focus and sweep the sound beam electronically. This capability enables rapid sectorial scans, improved probability of detection of complex flaws and greater control over beam incidence.

- Time-of-flight diffraction (TOFD) - TOFD uses a transmitter and a separate receiver set apart along the weld line. Rather than relying on specular reflection, TOFD records diffracted wave energy from crack tips. The arrival times of these diffracted signals permit precise sizing of crack height and estimation of growth rate under service loading.

- Full matrix capture (FMC) and total focusing method (TFM) - FMC records all element-to-element transmit-receive combinations in an array. Post-processing with TFM synthetically focuses the data across a region of interest, producing high-resolution, near-diffraction-limited images that improve detectability of complex-shaped defects.

- Guided wave ultrasonics - Guided waves expand along a structure and can travel many metres, enabling rapid screening for defects at remote or inaccessible locations.

Data display formats and what they mean

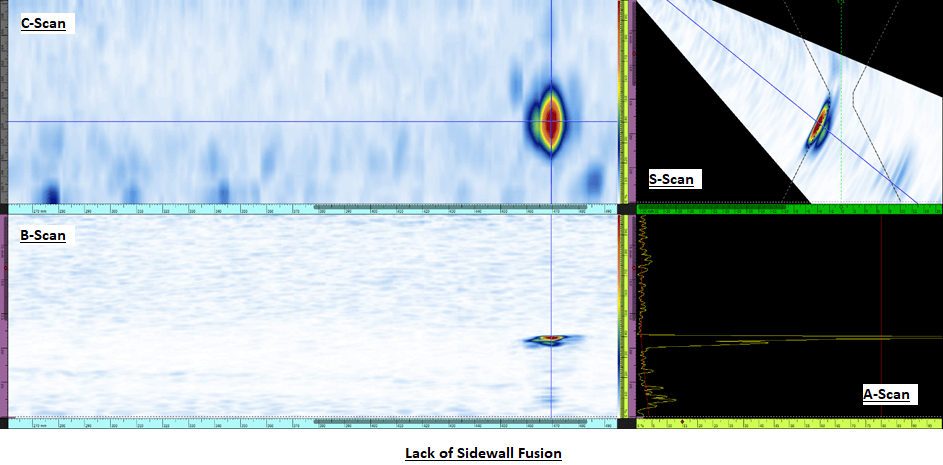

The data received from these techniques and methods are commonly displayed in formats known as A-scan, B-scan, C-scan, or S-scan. Understanding the differences between these formats is key to evaluating the results.

- A-scan - the basic single-channel display of amplitude versus time. A-scans are compact and ideal for thickness checks and simple front/back-wall identification.

- B-scan - a two-dimensional cross-sectional view (profile) produced by plotting A-scan amplitude along a linear scan, B-scans reveal the depth and approximate planar extent of reflectors in the scanned plane.

- C-scan - a plan (top-down) map showing the distribution of reflected amplitude, time-of-flight or derived thickness across an area. C-scans are useful for corrosion mapping and for presenting inspection results in an accessible visual format.

- S-scan - common in phased-array instruments, the S-scan (sectorial scan) displays a fan-shaped image produced by electronically steering an array. It provides a convenient view to assess weld geometry and detect inclined defects.

Interpreting displays often requires combining views. For example, a PAUT S-scan plus a TOFD record gives both angled-sector sensitivity and precise tip sizing.

Why is ultrasonic testing useful?

Ultrasonic testing occupies a central place in industrial inspection because it combines sensitivity, adaptability, and safety.

But at the same time, it is not a universal remedy. Let’s look at the principal strengths of ultrasonic methods with the practical constraints that shape their use in production, maintenance, and research.

The advantages of ultrasonic testing

The widespread adoption of ultrasonic testing is a testament to the myriad benefits of the method.

Ultrasonics interrogates the material volume, not merely the surface. The pulse-echo principle yields direct depth information, so defects may be located within a component rather than only indicated on its exterior. For many serviceability decisions, knowing the depth and approximate geometry of a reflector is more important than merely detecting its existence.

Shear waves and focused beams are particularly effective at detecting and sizing planar discontinuities such as cracks and lack-of-fusion in welds. When correctly tuned, ultrasonic methods can reveal small but critical flaws that may escape other inspection types.

Modern portable ultrasonic instruments combine rugged construction with fast, on-site measurement. This means that one can obtain thickness readings, locate discontinuities and deliver a preliminary assessment in minutes.

Unlike radiographic inspection, ultrasonic testing uses non-ionising sound waves and therefore does not require radiation protection measures, reducing regulatory burden and simplifying logistics.

From basic A-scan thickness checks to phased-array sectorial sweeps and FMC/TFM imaging, ultrasonic techniques scale across complexity levels. Phased-array and advanced post-processing provide refined spatial resolution and allow inspections that would have been impractical or impossible with early single-element instruments.

Although initial capital for high-end arrays and processing systems can be significant, ultrasonic testing frequently offers a good return on investment. Through reduction in unscheduled outages, more targeted repairs and the ability to track defect growth quantitatively, it enables condition-based rather than time-based interventions.

The limitations of ultrasonic testing

However, the limitations cannot be ignored.

Ultrasonic inspection is an interpretive skill. Probe placement, wedge selection, beam orientation and gain settings all influence results. Effective inspections require trained, certified personnel and reliable procedures.

Conventional contact UT requires good surface contact and a clean interface. Rough surfaces, corrosion scale, heavy paint or coatings, and complex surface geometry can all impede coupling or scatter energy, reducing detectability.

Additionally, certain materials present intrinsic difficulties. Coarse-grained metals, castings with large inclusions, and some stainless-steel castings scatter high-frequency energy and raise the noise floor. Composite materials, while often inspected ultrasonically in manufacture, may require specialised techniques and can present complex mode conversions that complicate interpretation.

Although pulse-echo needs only single-side access, complex geometries, tight radii and confined spaces can make it hard to maintain consistent probe orientation and coupling. Through-transmission requires two-side access, which may be impractical for in-service structures. Guided-wave methods address some access problems but introduce interpretation complexity.

Higher frequencies increase spatial resolution, but attenuate more rapidly. The trade-off sets a practical limit on the smallest detectable defect at depth. In very thick sections, or where attenuation is high, inspectors must accept lower resolution or adopt alternative modalities.

Conventional contact UT depends on a couplant. In freezing temperatures, high surface temperatures, or hazardous environments, maintaining adequate coupling is challenging. EMATs and air-coupled techniques reduce or remove couplant dependence, but have their own limitations.

Lastly, no single UT mode perfectly determines all defect parameters. Fitness-for-service decisions must account for measurement uncertainty and typically rely on conservative acceptance criteria, corroborative inspection or repeatability studies.

The Lab: home of non-destructive testing

When you need to inspect, test and evaluate a material, component, or assembly without destroying its serviceability, then you’ll want to make use of The Lab at Brookes Bell’s metallurgical survey, inspection, and non-destructive testing services.

The Lab brings together the world’s finest state-of-the-art equipment and technologies with highly-experienced experts to provide the very best inspection and testing services in the industry.

For more information, contact our team today for an obligation-free consultation.

Discover non-destructive testing at The Lab

For more of the latest news, information, and industry insights, explore The Lab’s News and Knowledge Hub…

Thermoset vs Thermoplastic: What’s the Difference? | Self-Healing Superhydrophobic Coating Delivers Unmatched Quality | What Metals Are Non-Ferrous?